The Definition of AI: Domains & Subdomains

According to MIT, Artificial Intelligence (AI) “refers to the development of systems that can perform tasks typically requiring human intelligence, such as reasoning, learning, and problem-solving.”

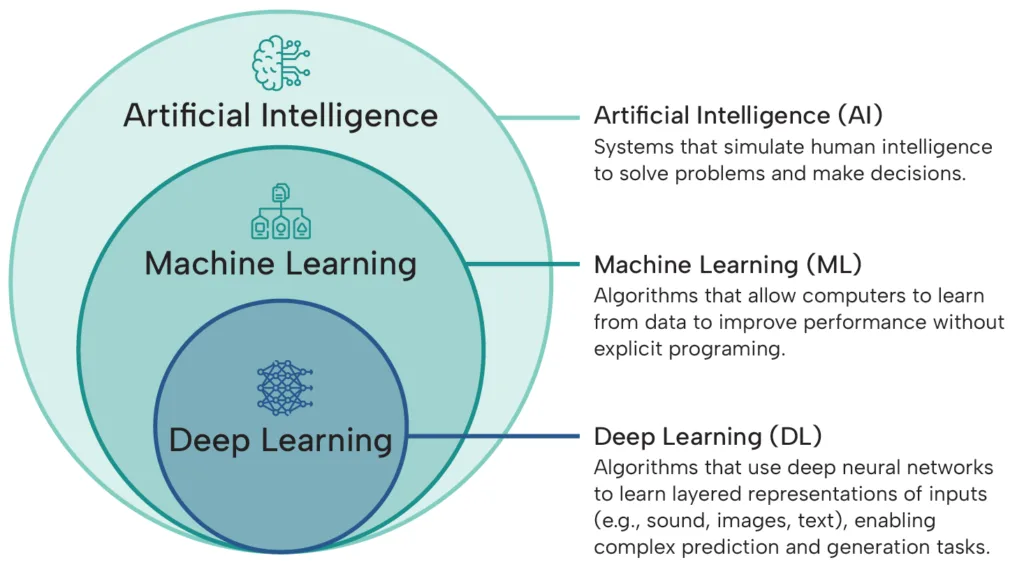

AI can be described as a hierarchy of domains. If we define AI as the scientific field of simulating human intelligence in machines, the next subdomain would be Machine learning (ML), which, according to NASA, “uses data and algorithms to train computers to make classifications, generate predictions, or uncover similarities or trends across large datasets.” In other words, ML learns from historical data and applies its learnings to new data.

Within ML, Deep Learning (DL) takes things further by using multi-layer neural networks—systems inspired by the human brain—that are able to automatically adjust their internal parameters during training as they ingest new data, enabling them to discover patterns and improve over time.

Within this hierarchy are applications with varied uses. For example, Generative AI is an applied version of Deep Learning models that can understand users’ natural-language requests to generate images, content, or information.

Similarly, facial recognition is an AI application that utilizes computer-vision algorithms (another branch of Deep Learning focused on enabling machines to interpret and analyze visual information) to detect, verify, and identify people based on their facial features.

Criteria: What Makes Something AI?

While there is no firm line separating “AI” from “Not AI” (especially not with the ever-expanding definition that seems to rebrand almost any advanced software or automation as ‘AI’), there are a few criteria that can be teased apart from the above and other definitions of AI.

Above all else, AI should simulate human intelligence. In practice, that can translate into…

- Autonomy. AI must be able to operate independently and without regular human intervention.

- Learning & Adaptability. AI systems must process and learn from data to identify patterns, improve performance, and generate solutions or new ideas.

- Perception & Understanding. AI can interpret input from the physical or digital world, including language, images, sounds, and sensor data.

- Decision-making & Reasoning. The system can evaluate input and make complex judgments without human intervention, selecting actions based on goals or rules.

- Goal-Oriented Behavior. The system is capable of addressing specific objectives and solving problems, rather than merely executing fixed instructions.

If we use these criteria, the distinction between AI and non-AI technologies becomes clearer.

For example, a customer support chatbot powered by Large Language Models (LLMs) is an example of AI. It understands natural-language inputs and generates human-like responses. It also operates autonomously, learns patterns from training data, and addresses inquiries, questions, and customer complaints in accordance with the company’s guidelines.

On the other hand, a thermostat using traditional if–then rule-based programming, which executes fixed instructions (e.g., if temperature is X, send alert), would not qualify as AI. While it operates autonomously, it does not learn, make decisions, or display goal-oriented behavior.

Changing Definitions: Impact of AI-washing

Like many terms, however, the definition of Artificial Intelligence continues to adjust as it becomes part of the public consciousness. AI has evolved from being primarily discussed in scientific papers and business-specific contexts (for example, YouTube has been moderating comments with the assistance of Machine Learning tools as early as 2017) to a global phenomenon at a breakneck pace.

Enter, AI-washing: the use of the suddenly-trendy “AI” label to exaggerate a technology’s capabilities to make it look more sophisticated or intelligent than it actually is—regardless of how (or even if) the product implements true AI.

Now, more products, fully or partially, carve out segments of the criteria to ride the AI buzz train. Some simply hedge, overstating basic algorithmic functions as “AI-powered” suites that claim to predict trends or generate insights, when in reality they rely on static models or rule-based logic.

Others stretch further, using the “AI” label to cover deterministic workflows or predictive dashboards that lack genuine learning or adaptability. And at the most egregious end of the spectrum, so-called “AI platforms” have been revealed to be little more than front ends for teams of offshore workers, with real people doing the bulk of the work.

This all-embracing definition of AI forces companies into a lose-lose choice. Adopt the ever-expanding approach to labelling AI and risk AI-washing, or adhere to scientific convention and risk being regarded as behind the times—a dangerous thing in an industry where innovation can be both the currency and the goal.

To further complicate things, AI’s entry into the public consciousness changes the stakes. At the core of it is the following question: “If AI learns from exorbitant quantities of data, where is that data coming from?”

For many users, their first foray into the world of AI has been through generative AI tools like ChatGPT, where the assumption is that AI models must continually ingest new data to sustain their dynamic learning capabilities. This data is often sourced from the web and other public environments, and, most critically, without the consent of the individuals involved. User privacy, of course, is not always a consideration.

Under this emerging, user-created definition, privacy and continuous dynamic learning are, in practice, treated as mutually exclusive in today’s AI landscape.

Facial Authentication (as we have defined it in prior pieces), or FA, would become an edge case in that tension. By requiring user consent, the FA data-point well becomes shallower, reducing its ability to learn and adapt in real time. But if we take the user-created definition of AI as true, then it must always be learning. If it isn’t, then is it really AI?

First, we need to discuss how AI learns to answer that question.

Static vs Dynamic Models

We have long held that Wicket’s Facial Authentication is a specific application of facial recognition, delineated explicitly for the product-wide privacy-first decisions that reduce the transfer of PII at every level of the product (the physical sensor, the embedded software, the back-end admin software that manages both of those, and so on and so forth).

If we hold that AI must meet the 5 criteria above, Facial Authentication comfortably meets four of the five outright.

- Autonomy. Facial authentication does not require human oversight once deployed; it operates independently in real time.

- Perception & Understanding. It perceives the world via sensor cameras, detecting faces and extracting features such as landmarks, geometry, and telemetry.

- Decision-Making & Reasoning. It makes decisions by matching the face presented to the sensor against the stored templates of enrolled individuals, calculating similarity scores, and determining the likelihood of identity.

- Goal-Oriented Behavior. Its objective is clear and narrow: verify face matches for access, authentication, or authorization.

Learning and adaptability are where we would theoretically hit a bump if we treated learning as something that can only occur in real time. This is true for humans, but AI does not need to dynamically learn—its algorithms can be updated at regular intervals using pruned data (collected with consent) that improves performance over time.

AI learns in two ways:

- Online or dynamic learning. The model is continuously, or at least frequently, trained using deployment data (i.e., it trains on the individuals or data points interacting with the AI).

- Offline or static learning. The model is trained once with carefully pruned data to remove redundant and erroneous data. After deployment, it can be updated or retrained, but this process doesn’t occur dynamically. When updated, the new data is also pruned.

There are advantages and disadvantages to each.

With online training, your AI can adapt to changes in the relationship between features and labels. It excels in unpredictable environments in which customization and strategic adjustments are paramount for success (e-commerce, for example).

Static AI, on the other hand, excels in stable environments where the inputs—such as faces—and the rules do not change frequently (e.g., repetitive tasks). It’s also more efficient, less resource-intensive, and more predictable (i.e., it performs consistently) because it does not constantly retrain on new data.

Static AI can also address bias amplification. Dynamic AI trains on the data it sees, meaning it can overtune itself to the data points it sees most frequently. By not continuously retraining on live data, static AI can avoid this (assuming, of course, that the algorithm was bias-tested at deployment). This is a critical point, allowing for human-in-the-loop verification of models—the failure of which could have real-world impacts.

However, static AI is at risk of model drift (i.e., it cannot adapt to immediate environmental changes), which can impact accuracy. However, if the training dataset is large and diverse enough to cover expected environmental changes (which are largely known in advance), it becomes a minor concern.

For opt-in-only biometrics, a static AI approach is the natural fit. The inputs and rules are stable, the environmental constraints are known in advance, and what matters most is consistent performance over time. Keeping the model static also strengthens privacy: training happens off-field and requires humans to select (acquire consent) and prune the data.

In short, static AI is the most responsible way to deliver biometric value while minimizing both privacy risk and bias amplification. And thus, this is the learning model that Wicket follows.

So, is Facial Authentication AI?

Yes.

While the definition of AI may be in flux, Wicket’s facial authentication platform satisfies the fundamental criteria of AI. It is autonomous, it perceives, it reasons, it is goal-oriented, and it learns.

By adopting a static AI approach, Wicket can test and benchmark performance in a controlled way. And most crucially, Wicket’s static model protects user privacy, mitigates bias creep, and delivers consistent performance (over 7 million authentication decisions and counting) in stable, real-world environments, such as stadiums and live events.

In a market crowded with AI-washing and moving goalposts, Wicket stands apart: applied AI, built responsibly, to solve clear, high-stakes problems at scale.